in search of queer gynae pioneers

Whilst exploring the catalogue and ‘cruising the collection’ I wanted to look for nods and winks of queerness especially related to any gynae pioneers and portraits (which I take a lot of in my creative practice). It’s challenging to locate LGBTQ+ content in traditional museum and archive collections, largely because of historical barriers in language and social openness. People didn’t describe themselves using terms like gay, queer, or LGBTQ+, because those identities were understood differently or because they were kept private out of necessity. Legal terminology frequently cast such identities in criminal terms, and many records don’t have any explicit LGBTQ+ labels at all.

I’ve been using Norena Shopland’s A Practical Guide to Searching LGBTQIA Historical Records, as a guide to address these challenges.

Working with the team at the Wellcome, we identified the following pioneers who would potentially identify as LGBTQ+ within a contemporary context.

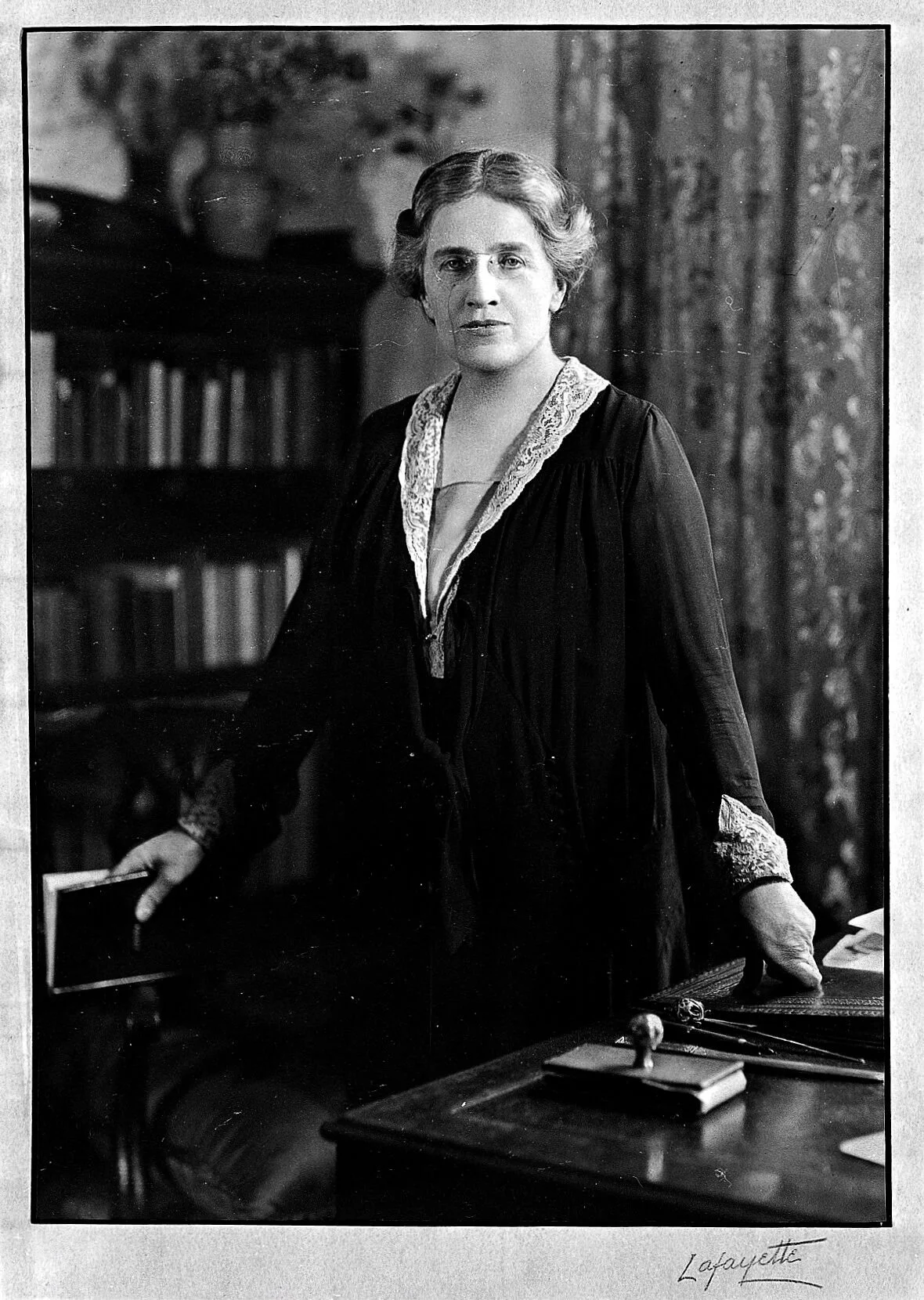

Christine Murrell

There’s no mention of Christine Murrell's sexuality in the Wellcome catalogue notes, and she doesn’t refer to herself using such terminology in her writing, likely due to the language conventions of the time.

Murrell (1874–1933) was an English medical doctor who lived with her companion Dr Honor Bone for over 30 years. A biography called *Christine Murrell M.D.* (1935) by Christopher St John was written at Honor’s request - the book acknowledges their shared living arrangement.

Christine met Honor early in her professional career, and together, they worked in general practice in West London. Murrell managed one of the first infant welfare clinics, assisted with the aftercare of imprisoned suffragettes, and became the first woman elected to the Council of the British Medical Association in 1924 and to the General Medical Council in 1933.

Her career began with roles in Northumberland and Liverpool before returning to London to work at the Royal Free Hospital, where she was the second woman to serve as a house physician. In 1903, she established a private practice in Bayswater with Honor. She participated in activism related to women's rights, including involvement in the women's suffrage movement prior to World War I. During the war, she served in and later chaired the Women's Emergency Corps. For two decades, Murrell delivered public lectures on women's health through the London County Council. Her 1923 book, *Womanhood and Health* presents both her medical knowledge and perspectives on women's health.

Murrell served on various committees within the British Medical Association and was elected as its first female member to the Central Council in 1924, serving until her death. In 1925, she conducted a survey on girls' menstruation experiences, which was published in *The Lancet* in 1930. She was the fifth president of the Medical Women's Federation from 1926 to 1928. In September 1933, Murrell became the first woman elected to serve as a representative on the General Medical Council but died on 18 October 1933 before assuming her position.

Louisa Martindale

Dr Louisa Martindale was born in 1872 and died in February 1966 at the age of 93. She spent more than thirty years with her companion, Ismay FitzGerald. In her 1951 autobiography A Woman Surgeon, she described her relationship with FitzGerald and reflected on experiencing love and happiness.

She pursued a medical career by studying at Royal Holloway, University of London, and then the London School of Medicine for Women, obtaining her Doctor of Medicine degree in 1905. At that time, women had only recently started receiving university degrees: University of London in 1878, Durham in 1895, Oxford in 1920, and Cambridge in 1948.

After working five years in Hull alongside Dr Mary Murdoch, a suffragist and the first woman doctor in Kingston upon Hull, Martindale returned to Brighton. She opened a medical practice and became Brighton’s first female general practitioner. In 1920, she contributed to founding the New Sussex Hospital for Women, serving as senior surgeon and physician until 1937, performing over 7,000 operations during her career.

Martindale addressed topics such as prostitution and venereal disease (now known as sexually transmitted infections) through published materials considered controversial at the time. She pioneered the use of X-rays and radium for treating fibroid conditions and breast cancer and participated in establishing the Marie Curie Hospital.

Her professional achievements include serving as president of the Medical Women’s Federation, becoming a Fellow of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, receiving a CBE, and being the first woman on the council of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists.

During World War I, she worked in France with the Scottish Women’s Hospitals, and during World War II, she served as a surgeon in London. Martindale also held roles as a magistrate, prison commissioner, and member of the National Council of Women.

The Louisa Martindale Building at the Royal Sussex County Hospital is named in her honour.

Michael Dillon

Laurence Michael Dillon was the first recorded trans man to undergo gender-affirming surgery.

Born in Kensington in May 1915, he recognised his trans identity early. After university, he started medical transition, receiving testosterone treatments. Outed at work, he lost his job but continued transitioning after meeting a plastic surgeon who performed his top surgery. This enabled him to change his birth certificate and legal name, allowing him to live authentically. He began medical studies at Trinity College Dublin, where he underwent additional surgeries with Harold Gillies, including a landmark phalloplasty.

Dillon published Self: A Study in Ethics and Endocrinology in 1946, which led to contact with Roberta Cowell, the UK's first trans woman to receive gender-affirming surgery. Their relationship ended when Cowell rejected Dillon’s marriage proposal. Dillon became a ship’s doctor before being outed by the press in 1958; he then relocated to India and became a Buddhist monk. He completed his memoir, Out of the Ordinary, shortly before his death in 1962 at age 47. The memoir, almost destroyed, was ultimately published in full in 2017.

Image credits below (l-r):

Dr Christine Murrell, Wellcome Collection.

Portrait of Louisa Martindale. President of the Med. Womens Fed. (1930-1932). Wellcome Collection.

This participatory research and socially engaged project is being delivered in collaboration with the Wellcome Collection.